This Saturday (August 10), Jo Fox will join the Westport Historical Society’s trip to Cockenoe Island.

She’ll walk the 28-acre spit of rock, brush and sand a mile off Compo Beach. For decades it’s been a favorite spot of birders, boaters and campers (and lovers).

Some members of the tour will be regulars. Others will see it for the 1st time.

None would be there, though, without Jo’s herculean efforts nearly 50 years ago.

Cockenoe Island.

In 1967 Jo Brosious was the editor of the Westport News — a fledgling newspaper, challenging the established (and establishment) Town Crier.

A newcomer from the West Coast, Jo and her husband enjoyed taking their small boat out to Cockenoe (pronounced kuh-KEE-nee), to fish and clam.

One day, they heard a rumor. The island would be sold. On it, a power plant would rise.

Jo started a campaign to keep Cockenoe in the public domain. Readers quickly responded.

A couple of months later, the Bridgeport Post ran an enormous headline: “UI Plans A-Plant in Westport.”

United Illuminating — a statewide utility, and the new owner of the island that had long been privately held — would not just build a power plant. They planned a nuclear power plant. A 14-story nuclear power plant.

With a causeway, linking the island to shore.

The Westport News swung into high gear. Jo wrote news stories and editorials decrying the idea. She published letters to the editor, and editorial cartoons.

The Town Crier, meanwhile, supported the plan. It would be good, the paper argued, for the town’s tax base.

Memorabilia in Jo Fox’s basement includes news clippings, a bumper sticker, a photo of Jo on Cockenoe, and another shot of her speaking in Hartford, as sunlight streams directly on her.

An RTM hearing drew an SRO crowd. The legislative body voted unanimously to acquire Cockenoe. They’d use federal, state and — if necessary — local funds to keep the island as open space.

Save Cockenoe Now — a grassroots group — met often at Jo’s house. They enlisted the help of a Westport Library research librarian. In those pre-internet days, she struck gold: a Life Magazine editorial about ways in which municipalities could curb eminent domain requests of power companies.

Jo’s group decided to challenge UI’s eminent domain, through a pair of bills in the state legislature. One would enable the town of Westport to use eminent domain in this case. The other would allow all Connecticut towns to have pre-eminence over all utilities, in all eminent domain cases .

That was huge. Case law was unsettled over who had 1st rights in cases involving eminent domain: utilities or local governments.

Ed Green ran for state representative, on a “save Cockenoe” platform. He became the 1st Democrat in 50 years elected from Westport.

Democrats pressed the issue. They rented buses to take Westporters to Hartford, for committee hearings on the 2 bills. Green introduced the 2 Cockenoe bills in Hartford. They were co-sponsored by Louis Stroffolino, a Republican representing the Saugatuck area.

Westport’s arguments were not against nuclear power, which — before Chernobyl and Three Mile Island — was considered safe and clean. The argument was for saving a valuable recreational spot; the power plant could be located elsewhere.

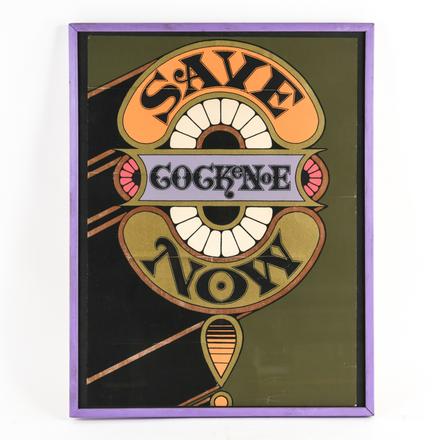

Naiad Einsel’s “Save Cockenoe Now” posters were seen all over Westport.

Under pressure — including national press like the New York Times and Sports Illustrated; Senators Abraham Ribicoff and Lowell Weicker; Congressman Stewart McKinney; conservationists, fishermen, thousands of citizens, and even other utility companies that feared the omnibus bill — UI offered to sell the island.

There was, however, one condition: Westport would drop the proposed legislation.

In 1967, the deal was done.

The town paid approximately $200,000 for Cockenoe Island — UI’s purchase price. State and federal funds covered 75% of the cost. Westport now owns Cockenoe — in perpetuity.

Jo trumpeted the accomplishment with this Westport News headline: “Isle Be Home For Christmas.”

When the deal closed — on December 23, 1969 — she wrote this head: “Cockenoe Island Safe in Sound.”

The next summer — and for every summer thereafter — area residents have enjoyed Cockenoe. But each year, fewer and fewer know that, without a crusade led by one woman, the island — if not the entire area — would look and feel far different today.

In July 1970, Life Magazine called it one of 7 significant environmental victories in the nation.

Jo Fox today.

Jo has been out to Cockenoe a few times since 1967 — but never in summer.

This weekend — 85 years young — she looks forward to seeing the birds, clams and boats. (Though perhaps not the lovers.)

Thanks to Jo Fox, the water there is also a lot less warm than it otherwise would be.

(This Saturday’s trip to Cockenoe begins at 11 a.m. at Longshore Sailing School. In addition to kayak rentals — available there — the cost is $18 for Westport Historical Society members, $20 for non-members. Click here for details.)